Learn how to build a DuckLake, snapshot by snapshot

Last updated: Dec 6, 2025

How does DuckLake work? What even is it? To find the answers to these questions, I used SEC financial data to build little local lakehouse.

DuckDB is a democratizing influence on data analysis and engineering. Because its creators obviously care about both design and performance, the tool gives more people a chance to do complex data-processing tasks without the mental, financial, and computational overhead that would come with doing such jobs on a cloud platform.

As I get better at using DuckDB, I also become more attentive to the nuances of how data is represented in various formats and schemas. With better conceptual understanding, I get more ideas of how far I can go by using DuckDB as the main (if not only) tool in my stack. So, when the DuckDB team announced its new DuckLake format, I looked forward to learning a new mode of working with datasets.

This tutorial distills what I learned. I’m starting from a fresh slate, so I proceed methodically, taking note of how each component changes with each data operation.

Short conceptual background

Here’s a little bit about Ducklake and the source data that I’m using. Skip to procedure.

The components

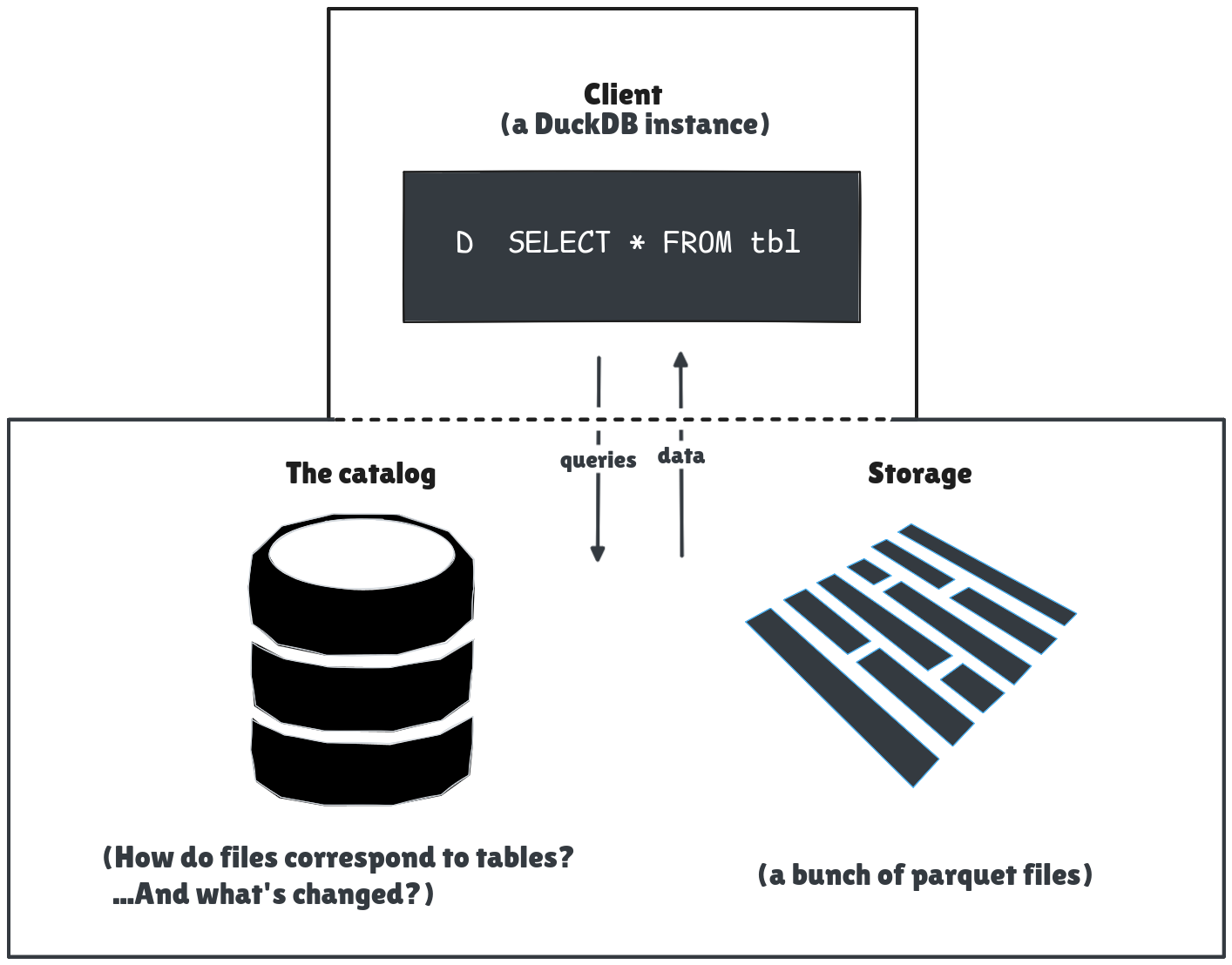

I assume that the client and catalog coordinate to ensure the user reads and writes to the correct files.

Ducklake has three components to think about: the client, the catalog, and the data files.

- The client. This is the SQL interface to model and query data.

- The catalog. A transactional database that tracks metadata. Catalog data includes information about schema versions, data changes, and the correspondence between data files and their tables.

- Storage. The data files that store all the rows of the DuckLake tables. In practice these are parquet files on a file system or in an object store.

When the client makes a statement that updates the schema, things change in the catalog. Any time the client adds or modifies data, things change in both the catalog and the data files. In this tutorial I try to highlight the corresponding changes that happen in each component with each modification.

The model

To be somewhat realistic, I chose a dataset of SEC filings. The SEC compiles all the statements they receive in a quarter in 4 related tables.

For this demo, I use only the num table, which records the value of transactions, and the sub table, which records information about submission and the company that made it.

Procedure

My configuration is as follows:

- Client: DuckDB

- Catalog: Sqlite

- Storage: Files on local computer.

There are many catalog DBs to choose from. I originally used a DuckDB database for the catalog, but it can handle only one client connection. That became annoying surprisingly quickly, so I chose SQLite for a local, multi-client experience.

For a production DuckLake, Object storage is a more likely choice than my local disk.

Prerequisites

First, set up the structure for the source files.

In a fresh directory, download one of the quarterly zip files—I use 2025q1. This zip is over 100MB, so downloading may take a moment.

Create a directory called

sources.Unzip the zip to the

sourcesdirectory.unzip 2025q1.zip -d sources/

The file set up looks like this:

.

├── 2025q1.zip

└── sources

├── num.txt

├── pre.txt

├── readme.htm

├── sub.txt

└── tag.txt

Then install DuckDB and the relevant extensions:

Install DuckDB if you haven’t already.

Open a DuckDB client and install the DuckLake and SQLite extensions.

INSTALL ducklake; INSTALL sqlite;

Attach the database

Attach the client to a new catalog database and specify the path to the data files:

ATTACH IF NOT EXISTS 'ducklake:sqlite:metadata.sqlite' AS ducklake_edgar

(DATA_PATH 'lake_files')

This creates a new catalog database file at metadata.sqlite.

├── 2025q1.zip

├── metadata.sqlite <-- catalog

└── sources

├── num.txt

├── pre.txt

├── readme.htm

├── sub.txt

└── tag.txt

The catalog initializes with all the DuckLake metadata tables.

Some tables, like ducklake_snapshot and ducklake_schema, already have rows.

To query metadata tables, use the identifier __ducklake_metadata_<DUCKLAKE_ALIAS>.<TABLE>.

For example, to query the ducklake_snapshot table:

FROM __ducklake_metadata_ducklake_edgar.ducklake_snapshot;

Appropriately, this “empty” snapshot is “Snapshot 0”:

┌─────────────┬───────────────────────────────┬────────────────┬─────────────────┬──────────────┐

│ snapshot_id │ snapshot_time │ schema_version │ next_catalog_id │ next_file_id │

│ int64 │ timestamp with time zone │ int64 │ int64 │ int64 │

├─────────────┼───────────────────────────────┼────────────────┼─────────────────┼──────────────┤

│ 0 │ 2025-11-22 10:40:04.206912-03 │ 0 │ 1 │ 0 │

Create a schema

To make a logical grouping of tables and relationships, create a schema.

USE ducklake_edgar;

CREATE SCHEMA IF NOT EXISTS fin_statements;

USE fin_statements;

Query the ducklake_snapshot_changes see if anything changed:

SELECT snapshot_id, changes_made

FROM __ducklake_metadata_ducklake_edgar.ducklake_snapshot_changes;

┌─────────────┬─────────────────────────────────┐

│ snapshot_id │ changes_made │

│ int64 │ varchar │

├─────────────┼─────────────────────────────────┤

│ 0 │ created_schema:"main" │

│ 1 │ created_schema:"fin_statements" │

└─────────────┴─────────────────────────────────┘

More information about the schema is in the ducklake_schema table.

Create tables

Now create the tables for the schema.

These tables correspond to the num and sub tables from the source dataset and follow their model.

To track data lineage, I also add loaded_at and source_file columns.

Notice also that I wrap the CREATE TABLE in BEGIN and COMMIT statements.

Each snapshot is tied to a database transaction.

So it’s all or nothing: a new snapshot is created only if the new tables are created, and each new table is created only if all the others are created too.

BEGIN;

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS submissions (

adsh VARCHAR,

cik INTEGER,

name VARCHAR,

sic SMALLINT,

countryba VARCHAR,

stprba VARCHAR,

cityba VARCHAR,

zipba VARCHAR,

bas1 VARCHAR,

bas2 VARCHAR,

baph VARCHAR,

countryma varchar,

stprma VARCHAR,

cityma VARCHAR,

zipma VARCHAR,

mas1 VARCHAR,

mas2 VARCHAR,

countryinc VARCHAR,

ein INTEGER,

former VARCHAR,

changed VARCHAR,

afs VARCHAR,

wksi BOOLEAN,

fye VARCHAR,

form VARCHAR,

period DATE,

fy SMALLINT,

fp VARCHAR,

filed DATE,

accepted DATETIME,

prevrpt BOOLEAN,

detail BOOLEAN,

instance VARCHAR,

nciks SMALLINT,

aciks VARCHAR,

source_file VARCHAR,

loaded_at TIMESTAMP

);

CREATE TABLE IF NOT EXISTS numeric_facts (

adsh VARCHAR,

tag VARCHAR,

version VARCHAR,

ddate DATE,

qtrs INTEGER,

uom VARCHAR,

segments VARCHAR,

coreg VARCHAR,

value DECIMAL(28,4),

footnote VARCHAR,

source_file VARCHAR,

loaded_at TIMESTAMP

);

CALL ducklake_edgar.set_commit_message('Matt Dodson', 'Creating the tables', extra_info => 'https://www.sec.gov/files/financial-statement-data-sets.pdf');

COMMIT;

I also use a special DuckLake function to add a commit message.

To read this message and a summary of changes from one snapshot to the next,

query the ducklake_snapshot_changes table:

FROM __ducklake_metadata_ducklake_edgar

.ducklake_snapshot_changes;

┌─────────────┬──────────────────────┬─────────────┬─────────────────────┬────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ snapshot_id │ changes_made │ author │ commit_message │ commit_extra_info │

│ int64 │ varchar │ varchar │ varchar │ varchar │

├─────────────┼──────────────────────┼─────────────┼─────────────────────┼────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ 0 │ created_schema:"ma… │ NULL │ NULL │ NULL │

│ 1 │ created_schema:"fi… │ NULL │ NULL │ NULL │

│ 2 │ created_table:"fin… │ Matt Dodson │ Creating the tables │ https://www.sec.gov/files/financial-… │

└─────────────┴──────────────────────┴─────────────┴─────────────────────┴────────────────────────────────────────┘

Besides the changes in the snapshot table, the catalog database now has data about the new tables.

Query the ducklake_table table to see it:

SELECT table_id, begin_snapshot, table_name, path

FROM __ducklake_metadata_ducklake_edgar

.ducklake_table;

┌──────────┬────────────────┬───────────────┬────────────────┐

│ table_id │ begin_snapshot │ table_name │ path │

│ int64 │ int64 │ varchar │ varchar │

├──────────┼────────────────┼───────────────┼────────────────┤

│ 2 │ 2 │ numeric_facts │ numeric_facts/ │

│ 3 │ 2 │ submissions │ submissions/ │

└──────────┴────────────────┴───────────────┴────────────────┘

Notice that these tables also have a path. This path tracks where the data files for the table are in storage. But no files exist yet, because no data has been loaded into the tables.

Load data

Now load data from the source TXT files.

At the time of writing, Ducklake does not support primary keys.

To avoid duplicate data, use the MERGE INTO statement to upsert data.

To explain the logic, here’s an annotated snippet of how the transformation into numeric_facts works:

MERGE INTO numeric_facts

USING (

SELECT

adsh::VARCHAR AS adsh,

tag::VARCHAR AS tag,

version::VARCHAR AS version,

STRPTIME(ddate::VARCHAR, '%Y%m%d')::DATE AS ddate,

qtrs::INTEGER AS qtrs,

uom::VARCHAR AS uom,

segments::VARCHAR AS segments,

coreg::VARCHAR AS coreg,

value::DECIMAL(28,4) AS value,

footnote::VARCHAR AS footnote,

'2025q1.zip'::VARCHAR AS source_file

FROM read_csv('sources/num.txt', delim='\t', header=true)

) AS source

ON numeric_facts.adsh = source.adsh

AND numeric_facts.tag = source.tag

AND numeric_facts.version = source.version

AND numeric_facts.ddate = source.ddate

AND numeric_facts.qtrs = source.qtrs

AND numeric_facts.uom = source.uom

AND COALESCE(numeric_facts.segments, '') = COALESCE(source.segments, '')

AND COALESCE(numeric_facts.coreg, '') = COALESCE(source.coreg, '')

WHEN MATCHED THEN DO NOTHING

WHEN NOT MATCHED THEN INSERT VALUES (

source.adsh, source.tag, source.version, source.ddate,

source.qtrs, source.uom, source.segments, source.coreg,

source.value, source.footnote,

source.source_file, CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

);- Merge the table numeric facts.

SELECTfrom the source file with some light transformation to validate data types.- Use the table’s composite key to check that the row does not already exist.

- When checking, coalesce nulls to avoid inserting duplicates (I learned from experience).

- When the keys don’t match, insert a new record into the table.

Here’s the full load statement.

BEGIN;

MERGE INTO submissions

USING (

SELECT

adsh::VARCHAR AS adsh,

cik::INTEGER AS cik,

name::VARCHAR AS name,

sic::SMALLINT AS sic,

countryba::VARCHAR AS countryba,

stprba::VARCHAR AS stprba,

cityba::VARCHAR AS cityba,

zipba::VARCHAR AS zipba,

bas1::VARCHAR AS bas1,

bas2::VARCHAR AS bas2,

baph::VARCHAR AS baph,

countryma::VARCHAR AS countryma,

stprma::VARCHAR AS stprma,

cityma::VARCHAR AS cityma,

zipma::VARCHAR AS zipma,

mas1::VARCHAR AS mas1,

mas2::VARCHAR AS mas2,

countryinc::VARCHAR AS countryinc,

ein::INTEGER AS ein,

former::VARCHAR AS former,

changed::VARCHAR AS changed,

afs::VARCHAR AS afs,

wksi::BOOLEAN AS wksi,

fye::VARCHAR AS fye,

form::VARCHAR AS form,

STRPTIME(period::VARCHAR, '%Y%m%d')::DATE AS period,

fy::SMALLINT AS fy,

fp::VARCHAR AS fp,

STRPTIME(filed::VARCHAR, '%Y%m%d')::DATE AS filed,

accepted::DATETIME AS accepted,

prevrpt::BOOLEAN AS prevrpt,

detail::BOOLEAN AS detail,

instance::VARCHAR AS instance,

nciks::SMALLINT AS nciks,

aciks::VARCHAR AS aciks,

'2025q1.zip'::VARCHAR AS source_file

FROM read_csv('sources/sub.txt', delim='\t', header=true)

) AS source

ON submissions.adsh = source.adsh

WHEN MATCHED THEN DO NOTHING

WHEN NOT MATCHED THEN INSERT VALUES (

source.adsh, source.cik, source.name, source.sic,

source.countryba, source.stprba, source.cityba, source.zipba,

source.bas1, source.bas2, source.baph,

source.countryma, source.stprma, source.cityma, source.zipma,

source.mas1, source.mas2, source.countryinc, source.ein,

source.former, source.changed, source.afs, source.wksi,

source.fye, source.form, source.period, source.fy, source.fp,

source.filed, source.accepted, source.prevrpt, source.detail,

source.instance, source.nciks, source.aciks,

source.source_file, CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

);

-- Numeric facts

MERGE INTO numeric_facts

USING (

SELECT

adsh::VARCHAR AS adsh,

tag::VARCHAR AS tag,

version::VARCHAR AS version,

STRPTIME(ddate::VARCHAR, '%Y%m%d')::DATE AS ddate,

qtrs::INTEGER AS qtrs,

uom::VARCHAR AS uom,

segments::VARCHAR AS segments,

coreg::VARCHAR AS coreg,

value::DECIMAL(28,4) AS value,

footnote::VARCHAR AS footnote,

'2025q1.zip'::VARCHAR AS source_file

FROM read_csv('sources/num.txt', delim='\t', header=true)

) AS source

ON numeric_facts.adsh = source.adsh

AND numeric_facts.tag = source.tag

AND numeric_facts.version = source.version

AND numeric_facts.ddate = source.ddate

AND numeric_facts.qtrs = source.qtrs

AND numeric_facts.uom = source.uom

AND COALESCE(numeric_facts.segments, 'none') = COALESCE(source.segments, 'none')

AND COALESCE(numeric_facts.coreg, 'none') = COALESCE(source.coreg, 'none')

WHEN MATCHED THEN DO NOTHING

WHEN NOT MATCHED THEN INSERT VALUES (

source.adsh, source.tag, source.version, source.ddate,

source.qtrs, source.uom, source.segments, source.coreg,

source.value, source.footnote,

source.source_file, CURRENT_TIMESTAMP

);

CALL ducklake_edgar.set_commit_message('Matt Dodson', 'Loaded data from 2025q1.zip');

COMMIT;

Now the tables have data. The ducklake_table_stats table provides a summary:

FROM __ducklake_metadata_ducklake_edgar

.ducklake_table_stats;

┌──────────┬──────────────┬─────────────┬─────────────────┐

│ table_id │ record_count │ next_row_id │ file_size_bytes │

│ int64 │ int64 │ int64 │ int64 │

├──────────┼──────────────┼─────────────┼─────────────────┤

│ 2 │ 3658551 │ 3658551 │ 118205163 │

│ 3 │ 6231 │ 6231 │ 826336 │

└──────────┴──────────────┴─────────────┴─────────────────┘

Loading data also created the data path, lake_files, as a directory.

And this path has parquet files:

.

├── lake_files

│ └── fin_statements

│ ├── numeric_facts

│ │ └── ducklake-019abaa3-3089-7fd2-ad3d-fbe1e49c555a.parquet

│ └── submissions

│ └── ducklake-019abaa3-2feb-7b74-9ea0-7e7f3ed49182.parquet

These parquet files are where the data exists.

Query the metadata about them through the ducklake_data_file table:

SELECT data_file_id, table_id, file_size_bytes, path, begin_snapshot, end_snapshot

FROM __ducklake_metadata_ducklake_edgar

.ducklake_data_file;

┌──────────────┬──────────┬─────────────────┬───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┬────────────────┬──────────────┐

│ data_file_id │ table_id │ file_size_bytes │ path │ begin_snapshot │ end_snapshot │

│ int64 │ int64 │ int64 │ varchar │ int64 │ int64 │

├──────────────┼──────────┼─────────────────┼───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┼────────────────┼──────────────┤

│ 0 │ 2 │ 118205163 │ ducklake-019abaa3-3089-7fd2-ad3d-fbe1e49c555a.parquet │ 3 │ NULL │

│ 1 │ 3 │ 826336 │ ducklake-019abaa3-2feb-7b74-9ea0-7e7f3ed49182.parquet │ 3 │ NULL │

└──────────────┴──────────┴─────────────────┴───────────────────────────────────────────────────────┴────────────────┴──────────────┘

Time to query the actual data.

Query

Query the top three firms that reported the most profit on their annual report for 2024-12-31 (and who filed an annual report in this batch of SEC data).

This query joins the two tables to relate the numeric entries with the information about the company that submitted the entry.

SELECT name, value / 1000000 "net_income_millions", ddate period_end, filed date_filed

FROM numeric_facts num

INNER JOIN submissions sub ON num.adsh = sub.adsh

WHERE tag = 'NetIncomeLoss'

AND form='10-K'

AND uom='USD' AND segments IS NULL

AND ddate='2024-12-31'

ORDER BY net_income_millions DESC

LIMIT 3;

┌────────────────────────┬─────────────────────┬────────────┬────────────┐

│ name │ net_income_millions │ period_end │ date_filed │

│ varchar │ double │ date │ date │

├────────────────────────┼─────────────────────┼────────────┼────────────┤

│ ALPHABET INC. │ 100118.0 │ 2024-12-31 │ 2025-02-05 │

│ BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC │ 88995.0 │ 2024-12-31 │ 2025-02-24 │

│ META PLATFORMS, INC. │ 62360.0 │ 2024-12-31 │ 2025-01-30 │

└────────────────────────┴─────────────────────┴────────────┴────────────┘

The actual process of working with and cleaning this dataset is a topic of its own. In short, firms have different fiscal years and apparently have full discretion over how they tag each financial statement. Take care when comparing data across firms and submissions.

Anyway, this article is about DuckLake, so let’s get back to the metadata.

Delete

Intel has performed quite poorly and frankly I’d prefer to think it never existed.

Let’s delete all Intel entries from the numeric_facts table:

BEGIN;

DELETE FROM numeric_facts

USING submissions sub

WHERE numeric_facts.adsh = sub.adsh

AND sub.name ILIKE '%INTEL%';

CALL ducklake_edgar.set_commit_message('Matt Dodson', 'Getting rid of Intel data');

COMMIT;

To confirm:

SELECT count(*) FROM numeric_facts num

INNER JOIN submissions sub

ON sub.adsh = num.adsh

WHERE sub.name ILIKE '%INTEL%';

┌──────────────┐

│ count_star() │

│ int64 │

├──────────────┤

│ 0 │

└──────────────┘

This delete creates a new snapshot:

SELECT snapshot_id, changes_made, commit_message

FROM __ducklake_metadata_ducklake_edgar

.ducklake_snapshot_changes

ORDER BY snapshot_id DESC

LIMIT 1;

┌─────────────┬──────────────────────┬───────────────────────────┐

│ snapshot_id │ changes_made │ commit_message │

│ int64 │ varchar │ varchar │

├─────────────┼──────────────────────┼───────────────────────────┤

│ 4 │ deleted_from_table:2 │ Getting rid of Intel data │

└─────────────┴──────────────────────┴───────────────────────────┘

Interesting. The delete also creates a new file in storage.

lake_files/fin_statements/numeric_facts

├── ducklake-019abaa3-3089-7fd2-ad3d-fbe1e49c555a.parquet

└── ducklake-019abac9-2488-7301-be20-09fd7b27f0d6-delete.parquet

For a record of these delete files, query the ducklake_delete_file table:

SELECT delete_file_id, table_id, delete_count

FROM __ducklake_metadata_ducklake_edgar

.ducklake_delete_file;

┌────────────────┬──────────┬──────────────┐

│ delete_file_id │ table_id │ delete_count │

│ int64 │ int64 │ int64 │

├────────────────┼──────────┼──────────────┤

│ 2 │ 2 │ 4885 │

└────────────────┴──────────┴──────────────┘

In summary, all data changes are tracked at each snapshot. This might be useful.

Time travel

As it turns out, my delete operation was overzealous.

With my sloppy WHERE clause, I deleted not only the records for Intel but also all records for all companies with something about “intelligence” in their name.

Besides, I discovered that deleting unpleasant data does not necessarily delete unpleasant emotions.

Fortunately, DuckLake snapshots preserve the data changes. Using the time travel feature, I can query old snapshots.

From the snapshot_changes table, I see that the delete happened in Snapshot 4.

To get the data before the delete, query with AT (VERSION => 3):

SELECT count(*) FROM numeric_facts num AT (VERSION => 3)

INNER JOIN submissions sub

ON sub.adsh = num.adsh

WHERE sub.name ILIKE '%INTEL%';

┌──────────────┐

│ count_star() │

│ int64 │

├──────────────┤

│ 4885 │

└──────────────┘

You can review all changes from one snapshot to the other with the Data change feed function.

Recover

Here’s a short way to restore numeric_facts to the table from an old snapshot (thanks to a user on the DuckDB discord for the tip).

BEGIN;

CREATE OR REPLACE TABLE numeric_facts AS (FROM numeric_facts AT (version => 3));

CALL ducklake_edgar.set_commit_message('Matt Dodson', 'Going back to the way things were');

COMMIT;

Find old data files

With all the changes, some of my data files are no longer needed.

You can expect this by checking the ducklake_data_file.

For example, the data in file 0 was relevant between snapshots 3 and 5:

FROM __ducklake_metadata_ducklake_edgar.ducklake_data_file

WHERE end_snapshot IS NOT NULL;

┌──────────────┬──────────┬────────────────┬──────────────┬

│ data_file_id │ table_id │ begin_snapshot │ end_snapshot │

│ int64 │ int64 │ int64 │ int64 │

├──────────────┼──────────┼────────────────┼──────────────┤

│ 0 │ 2 │ 3 │ 5 │

└──────────────┴──────────┴────────────────┴──────────────┘

Maintain

One thing that surprised me at first was that until the user takes action, the number of total data files grows with almost every write operation. Besides delete files, inserting more data into a table adds a data file (and the catalog tracks how the rows start and end across files)

Now I understand that this write-only approach is the normal way of working with parquet and data lakes. Besides preserving history and read and write performance, object storage is cheap.

Nevertheless, the structure of the data files can weigh on performance and costs. The DuckDB extension has a number of maintenance functions to manage this.

Final thoughts

I enjoyed learning about DuckLake. Even if I just continue to use it locally, the catalog and multi-client experience make it a nice alternative to a “classic” DuckDB database file.

With no implementation experience and only a vague idea of how data lakes and catalogs work in general, it took me some time to wrap my head around how DuckLake works as an application and data architecture. I feel I have a solid intuition of how things work, and I hope this tutorial has helped you feel the same way.

Ideas to go further

To learn more about how DuckLake works, try these operations and explore how the changes manifest in the catalog and storage.

- Load more data

- Document your tables with comments

- Do an

UPDATE(check for snapshot expirations) - Alter a table (what metadata tables will change?)

- Change the config

For ideas about using Ducklake in the wider data engineering ecosystem, you can try these:

- Change the storage to S3 or something similar

- Go further with the downstream transformations, building marts and views that can actually serve for financial screening and analysis

- Incorporate transformation tools like dbt or orchestration tools like Dagster to build full data pipelines

Good luck!